What Is Russian Flypaper? A Closer Look at This Time-Tested Insect Trap

A classic red strand of Russian flypaper gently swaying in a sunlit breeze — simple, silent, and surprisingly effective.

There’s a quiet moment in a rustic wooden cottage where time seems to pause — a single housefly buzzes erratically near the kitchen window, drawn by warmth and light. Then, a fluttering red thread catches its wing. Struggling briefly, it becomes another speck on a long strand of sticky silence. This is the uncelebrated triumph of Russian flypaper: an old-world solution that still holds its ground in our high-tech age.

The name itself evokes intrigue — “Russian flypaper.” It conjures images of icy winters, secret Soviet labs, or perhaps a folk remedy passed down from babushkas in remote villages. Was it born in the shadow of the Kremlin? Did Cold War scientists refine it to perfection? The truth is both simpler and more poetic. This humble trap has no ties to espionage, but rather to centuries of rural ingenuity — a testament to how necessity breeds not just invention, but elegance.

In 19th-century Russian homes, flypaper was both practical tool and subtle cultural symbol — sometimes even used in festive settings.

Long before electric zappers or aerosol sprays, life in rural Russia demanded cleverness. With no access to modern pest control, households relied on what nature provided. Enter the original Russian flypaper: a cotton strip coated in a blend of natural resins, honey, and pine sap, dyed deep red or amber. The result? A slow-moving ribbon of sweetness that lured flies with scent and color, then held them fast with a gentle but relentless grip.

But its role went beyond mere utility. In some regions, colored flypapers were hung during celebrations — weddings, harvest feasts — not only to keep pests away, but as symbolic wards, blending superstition with sanitation. The same strip that trapped a fly might also carry wishes for health and abundance, quietly merging function with folklore.

Today, science reveals why this analog trap still works so well. Flies are guided by three primal instincts: light, motion, and smell. Russian flypaper exploits all three. Its bright hue mimics fruit or fermenting matter; its dangling movement simulates life; and its faintly sweet aroma whispers of decay and nourishment. Unlike electronic devices that require power and produce noise, or chemical sprays that disperse toxins, flypaper operates in silence — a passive intelligence that waits, watches, and captures without disturbance.

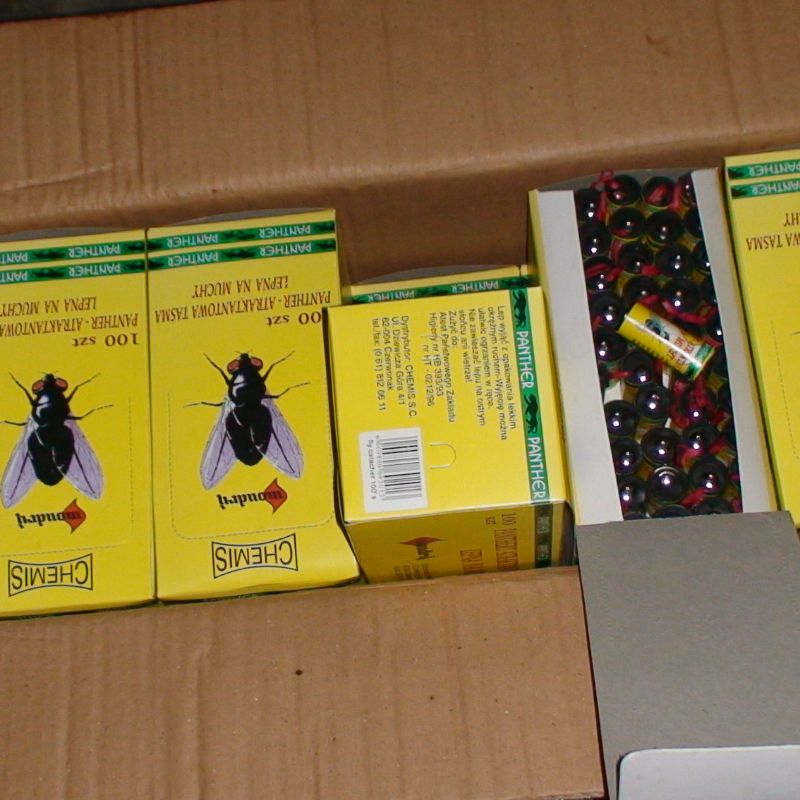

Modern versions maintain traditional design while improving adhesive consistency and safety for indoor use.

During the Soviet era, when resources were scarce and innovation often meant doing more with less, flypaper became a state-supported staple. Factories mass-produced standardized strips, distributing them across cities and collective farms. Surprisingly, declassified archives even mention a peculiar diplomatic anecdote: a Soviet embassy allegedly used specially treated flypaper to detect insect-sized surveillance devices — tiny mechanical “bugs” that, like real ones, could be caught on sticky surfaces.

Beyond its practicality, the image of flypaper entered Russian literature and cinema as a quiet metaphor — for endurance, for the persistence of daily life under hardship. It was never glamorous, yet always present, much like the people who used it.

In today’s world, where urban gardeners grow basil on balconies and pet owners seek non-toxic ways to protect their animals, Russian flypaper has found new relevance. Organic farmers use it to monitor whitefly populations without pesticides. Eco-conscious households hang it near compost bins to deter fruit flies. Pet parents appreciate its safety — no fumes, no risks if a curious cat bats at it.

And thanks to the handmade revival, DIY kits featuring organic adhesives and essential oil infusions have become popular at green markets. These modern iterations honor tradition while embracing sustainability — proof that old solutions can evolve without losing their soul.

The design itself has been refined through observation and experimentation. Studies show that certain colors dominate in effectiveness: deep red and golden yellow attract up to 70% more flies than green or blue. Why? Because these hues resemble overripe fruit and flowers — key food sources for many flying insects. Some advanced versions now include micro-capsules of yeast extract or fermented fruit essence, slowly releasing scents that mimic ideal feeding grounds.

Yet the greatest lesson flypaper offers isn’t about killing pests — it’s about awareness. Each captured insect tells a story. A sudden spike in trapped flies may signal a hidden spill or damp corner. Changes in species reflect shifts in outdoor ecology. In this way, the paper becomes a living journal of your environment — not a weapon of war, but a mirror of balance.

Perhaps that’s why, after more than a century, this quiet thread still swings in kitchens around the world. It doesn’t promise total victory over nature. Instead, it acknowledges coexistence — imperfect, messy, and honest. Every tiny footprint left in the glue is a reminder: sometimes, the simplest tools reveal the deepest truths.